Sm(art): The Visibility Project

Bitch MediaSM{ART}: THE VISIBILITY PROJECT

by Kat Kimberley

Published on February 20, 2010

What makes “good” Art?

Despite what museums curators, art critics, and other “established” representatives tell you, “good art” usually boils down to a matter of individual taste. Me, I get bored looking at bucolic landscapes paintings. Did I mention those child angels from the Victorian Era really creep me out? Yeah, I know, I’m supposed to enjoy the soft pastels of Monet or the drooping clocks of Dali. But I don’t. Given the choice, I’ll take a screenprint by Favianna Rodriguez over a Warhol or a Jennifer Linton over a Degas.

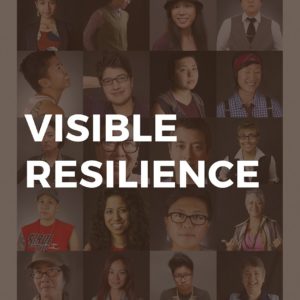

Most of the art our culture celebrates is the same type of art that makes me yawn. See, I enjoy art that gets my blood racing. For me, good art needs to be both aesthetically appealing and make my brain hurt. Because of my intense predilection for this type of provocative eye candy, I was exceedingly pleased recently to discover the Visibility Project—a female, Asian American, Queer portraiture project by Bay Area Photographer Mia Nakano and Los Angeles collaborator Christine Pan.

At an art gallery called Seed Corn in San Francisco, I stumbled upon their work. The gallery is operated by The Greenlining Institute as part of a broader Community Arts Initiative which “serves as a way to acknowledge the debt that social justice movements owe artists.” Bingo! I rushed inside—this sounded like just my cup of tea!

From across the room, a single photograph caught my eye. As I approached the portrait to look into the eyes of the subject my mind spewed out categories “Woman” “Asian” and “Queer.” But just as soon as I had pegged this person into narrow, culturally defined pigeonholes, I began to be troubled by my reductive thinking. My conscious grew angry at my brain. Why couldn’t my mind view a face without forcing it into a constructed category? Was gender and sexuality somehow being performed in these photos? How could I relate without stereotyping?

Little did I know, the internal moral tug-o-war taking place within my head over these shifting categories was the expressed intention of the artists. The Visibility Project was launched in 2008 by Photographers Mia and Christine as a way to present the strength, emotion, passion, and diversity that exist within the Queer Asian American community. Nakano and Pan began the project by putting out emails to their networks for 12-15 Asian American persons who identified as queer females, whether it be a lesbian, bisexual, mtf, ftm, or genderqueer orientation. The email was simple and said “come as you are.” There was no stylist or make-up artist, or prearranged wardrobe. The response they got was overwhelming and the show quickly expanded to 40+ participants.

Recently, I spoke with Nakano about her interests in photography and the intersections between race, gender, and sexual orientation in her work. She described her inspiration stemming from her travels to Nepal as a photojournalist where she documented Nepali GLBTQI human rights workers of the Blue Diamond Society, the largest queer rights organization in Nepal. “It was phenomenal to engage with queer rights activists who put their lives on the line by being out and being visible.” She continued, “Once, I rode on a bus for an hour with a BDS activist to reach a “possible” lesbian, to let her know that yes, there were other people like her, and a small but dedicated community who would support her. “

Since retuning to the States and founding the Visibility Project with Christine Pan, the work has rapidly taken on a life of it’s own thanks to generous support from AQWA (Asian and Pacific Islander Queer Women and Transgender Activists) RayKo Photo Center and Astraea. The project has moved beyond photos to include video segments with participants speaking about issues like Proposition eight, gender and sexual identity, as well as the process of coming out in multi-ethnic communities. The portraits have been featured in a handful of galleries throughout California and the project is now expanding to include participants in cities across the country, and will culminate in a book and short documentary film.

If you ask me, these are not only beautiful portraits, but on a deeper level, they help to humanize the diversity and complexity embedded within constructed categories. That’s what I call good art! While the Visibility Project photos may never be canonized, or widely appreciated, they encourage the viewer to not only appreciate fine art, but in doing so, to contemplate identity, culture, ethnicity, representation, and sexual orientation. Now, I admit I’m no expert on fine art but when’s the last time a Monet Lilly pad or a Degas ballerina made you do all that?